“Write what you know”—and its many opposing suppositions—is perhaps the most commonly touted fiction-writing maxim; it has been defined, re-defined, debated, refuted, defended, and all the while handed down to fledgling writers as the ultimate golden rule. A few years ago, a fiction novice starting out on her first attempt at a novel, I took this well-worn advice and ran with it—in the exact opposite direction. Absurdly, I didn’t trust myself with the material of my own life; I felt that as long as I was dabbling in personal experience I would never truly understand how to create story. It seemed to me that in order to become a writer I had to weave the story fabric from nothing—from thin air and fancy—before I could be convinced of myself as “writer.” It is this dubious logic that led a Yorkshire lass, raised in a post-industrial waste of a town in the north of England, to set her first novel in New Orleans. Who knows what naive and masochistic part of me insisted on this task, but insist it did, and years on it is a task I am still trying to complete.

“Write what you know”—and its many opposing suppositions—is perhaps the most commonly touted fiction-writing maxim; it has been defined, re-defined, debated, refuted, defended, and all the while handed down to fledgling writers as the ultimate golden rule. A few years ago, a fiction novice starting out on her first attempt at a novel, I took this well-worn advice and ran with it—in the exact opposite direction. Absurdly, I didn’t trust myself with the material of my own life; I felt that as long as I was dabbling in personal experience I would never truly understand how to create story. It seemed to me that in order to become a writer I had to weave the story fabric from nothing—from thin air and fancy—before I could be convinced of myself as “writer.” It is this dubious logic that led a Yorkshire lass, raised in a post-industrial waste of a town in the north of England, to set her first novel in New Orleans. Who knows what naive and masochistic part of me insisted on this task, but insist it did, and years on it is a task I am still trying to complete.

Whatever side of the “write what you know/write what you don’t know” dichotomy you fall on, there are almost irrefutable benefits to drawing from a subject you know intimately, and after my year in GrubStreet’s Novel Incubator, I would argue that this is especially true of setting and place. My fellow Incubees (Novel Incubator class of 2014-15) set their novels in places as disparate as Kanpur, India; Herzliya, Israel; and rural Nebraska, but the common denominator was the writer’s familiarity with each of these settings. Each of these novelists had a significant personal connection to their chosen setting, and their prose carries the authentic weight of their knowing that place, drawing from their reservoirs of specificity and detail that create on the page a world palpably real.

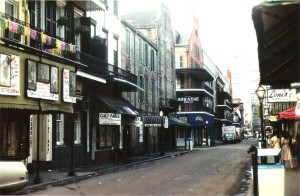

The importance of a strong sense of place varies from novel to novel, depending on what the writer is trying to achieve, but it is often a crucial element of creating that illusory note of “reality” or “authenticity” (two abstractions we set much store by, however impossible they are to describe) that writers of fiction seek. In the case of New Orleans, a city known globally for its distinctive culture and unique architecture, an authentic sense of place seems vital whether it is integral to the writer’s project or not. For me, all of this amounts to a potentially overwhelming and intimidating lack of knowledge that has, on more than one occasion, prompted me to abandon the novel entirely. I’ve spent countless hours fretting over the potential futility of my efforts: How will I ever “know” enough about this city? How will I ever compensate for not being a local? Where do I even begin?

The answer came in the form of a book I came across by chance, a study of post-Katrina New Orleans titled We’re Still Here Ya Bastards: How the People of New Orleans Rebuilt Their City, by Roberta Brandes Gratz. (And “by chance,” I mean“I picked it off the shelf because it had a swearword in the title.”) I’m only halfway through, and I finally feel like I am gaining a sense of New Orleans. The book focuses, of course, on Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Though Katrina is tangential to my novel’s central plot—in my first draft it barely figured at all—I am discovering that to learn about the storm and the struggles of neighborhoods and communities to rebuild is to learn about contemporary New Orleans. Through this lens, I am gaining a solid grasp of the city’s layout and geography, the history of its settlement, industry, boom years and bust years, the unique architecture and plant life, the tight knit family communities in the Lower Nine. And, most of all, the unique resolve of New Orleanians to return, to rebuild, to restore their city from the ground up.

This experience is teaching me that sometimes research does not come in the form one expects. I never thought of my novel as being “about” Katrina, and even though the storm now has a greater presence in the narrative, most of what I’ve learned about the disaster itself will never make it into the text. But, when looking for a “way in” to researching such an unwieldy topic, it can be really useful to focus on one specific area and gain an understanding of the wider, more diffuse elements of your subject, like a city’s cultural history, through that focused lens. Wrapped up in my Boston apartment with this book, I feel in many ways closer to grasping a sense of New Orleans than I did walking the city’s streets on a research trip I took last summer.

Though we’re not sure where, exactly, “write what you know” originates—some attribute it to Hemingway—I have always associated the concept with Henry James’ essay, “The Art of Fiction,” in which he remarks, “it is equally excellent and inconclusive to say that one must write from experience,” and goes on to assert that experience is “never limited and it is never complete… It is the very atmosphere of the mind.” James advocates for a version of “writing from experience” that allows for the definition of “experience” to include the most fleeting of impressions. The glimpsed moment that creates a picture in the mind, suggests James, constitutes experience. Though I’ll probably never claim to know New Orleans, fortified by this expanded concept of writing “from experience,” I’m learning as much as I can about Katrina, in the hope that this singular event will become the impression through which I catch a glimpse this most singular of places.