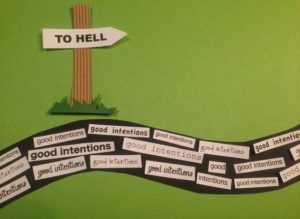

Just as the road to Hell is paved with good intentions, the path to my recycle bin is littered with fuzzy intentions. One of these scenarios tells a complete story. The other is just a pile of garbage.

Let’s consider: “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions,” (originally said by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux in the eleventh century, not Samuel Johnson as it is often attributed to.)

There’s a story there. Can you see it? There is a clear direction. Someone is headed to Hell. We  know the protagonist’s intentions are good. But something happens. A complication. A series of complications which progressively undo all those good intentions one at a time, breaking our hero down, building toward a dramatic finish. That character who walked in the first scene with the best of intentions irreversibly changes course. And she ends up in Hell.

know the protagonist’s intentions are good. But something happens. A complication. A series of complications which progressively undo all those good intentions one at a time, breaking our hero down, building toward a dramatic finish. That character who walked in the first scene with the best of intentions irreversibly changes course. And she ends up in Hell.

I don’t necessarily want my characters to end up in Hell, but I do want them to end up in a place or state they earn as a result of their actions. So I grab my characters by the collar and shout at them, plead with them, to answer one important question: What are your intentions?

I find myself obsessively asking my characters this question every time they walk into a room. What do they want? Why are they in this particular place on this particular day?

They don’t always answer me.

In every chapter, in every single scene, each person in the room must want something. And they shouldn’t all want the same thing. Opposing interests create tension. Tension holds the reader’s interest.

Once I corner my characters and force them to reveal their intentions, I ask myself: How can I complicate the scene so they don’t all get what they want? What is the consequence of them either getting what they wanted, or failing to get it? What changes? And most importantly, how do these consequences forward the plot?

If I can’t identify the intentions, complications, consequences, and impact of a scene, I probably need to cut it because it is not necessary to the plot. I’ve cut so many scenes.

As I thrust these questions on the fictional people in my life, I find myself projecting them on real people too. When a fellow parent at the middle school suggests we grab a coffee, I wonder if they are going to ask me to volunteer for a committee. When my kids call from college “just to say hi,” I think, “Hmmmm, what is their intention?” (But, honestly, in that case, I don’t even care. I’m just glad they call!)

I even do this to myself. What do I want? What, exactly, are my intentions?

If I’m the character in a book someone else is writing, I hope the Author is reading this. I will make this easy for you, Author. I will tell you exactly what my intentions are: I intend to finish my book (as soon as I finish this blog post). Then I intend to find an agent who loves my book, someone who also sees potential in my next book, because I’ve already started outlining that one too. Oh, and I intend to find a publisher who is excited about my writing. Then I will write more books.

Author, are you listening? These are my intentions.

But I know how this works. I get it. You, Author, can’t make this easy on me or I would be a boring character. It would be a boring book. So you throw in complications. Sick kids. Family obligations. Burst pipes. People who don’t like my writing. Writer’s block. A crashed computer. A health crisis. A presidential election that upends everything I have ever believed in.

So, like the characters I write, I have to pivot when confronted with a complication. In one “scene” I showed up at a Literary Idol event and submitted my first page to be read aloud and critiqued in front of a crowd. My intention was to get feedback and maybe some reassurance that I was on the right track. I felt confident. I settled into my seat and held my breath.

Complication: I got ripped to shreds by the literary agents on the panel. Thank God it was anonymous and no one in the room noticed me shrinking into my chair as the agents discussed the numerous flaws in my work.

Consequence: I seethed for about twenty-four hours. But then I reflected on what those agents said. My opening was cliché. I hadn’t recognized it before, but yes, they were right. And I had started in the wrong place. I trashed that opening scene and started over.

How does the consequence fit into the larger plot? I slowly regained my confidence. I’ve since submitted that revised opening scene to four contests. I even won some of them. I moved forward toward my goal.

I went to that Literary Idol event with the intention of hearing positive feedback. Instead, I was stripped down, publicly humiliated. But I learned something. I adapted and the consequence was a good one, although not the one I initially wanted.

I see what you did there, Author. I do it to my characters too. Like me, my characters don’t always need the thing they think they want. Things don’t always work out. Not every ending is happy.

But whether a writer is building toward a happy, sad, or ambiguous ending, the writer and the characters must earn that ending. These scenes – all these intentions and consequences — must build on each other in a meaningful way so that when we arrive at the ending, it satisfies. The character must deserve that ending, whether it is a place in Hell or a book contract.

If the agents at that Literary Idol event had nodded and said “Nice job,” I would have felt pretty good, maybe relieved, that day. But I wouldn’t have worked so hard to rewrite the opening. I wouldn’t have learned anything. It would have been a flat scene.

Or if they heaped praise on me and fought amongst themselves to represent me, it would have been anticlimactic. I wouldn’t have earned it. It would have been a boring story to read. (Although, let’s be honest, I would have been happy with boring in this circumstance.)

I understand that you, Author, need to toy with me, just like I toy with my characters. I understand that the consequence in each scene must lead to the next scene. It must move the narrative forward.

Some readers hate happy endings. They prefer natural consequences or unanswered questions. As a writer, I have a hard time making bad things happen to characters I like. Several writing instructors have pointed this out to me over the years. I’m working on being tougher.

As I edit, I continue to scrutinize every single scene, analyzing the intentions of each character. I want to earn that ending — happy or not.

Author, if you are still reading this, I want you to know I’m a-okay with happy endings, particularly when it comes to that book you are writing about me, the one where I finish my manuscript, find my dream agent, and get a book contract. I’ll do my best to earn it.

I vow to help you string those intentions, consequences, and scenes together. I will try to accept the complications and setbacks gracefully. But can we keep our focus on that happy ending, please?

2 comments