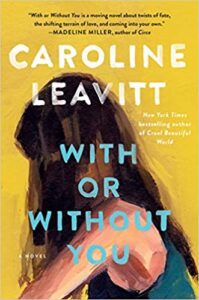

When Stella, a nurse who should know better, takes an unidentified pill from her washed-up rock star boyfriend’s pocket and slips into a coma, everyone around her is changed, especially her. She wakes up from her sleep to discover that her best friend, a doctor at the hospital, has come around on her boyfriend, and that her boyfriend has surprised even himself by choosing to be by her bedside instead of jumping at his last chance at super-stardom. As for Stella? She doesn’t know how or why, but she won’t stop drawing.

When Stella, a nurse who should know better, takes an unidentified pill from her washed-up rock star boyfriend’s pocket and slips into a coma, everyone around her is changed, especially her. She wakes up from her sleep to discover that her best friend, a doctor at the hospital, has come around on her boyfriend, and that her boyfriend has surprised even himself by choosing to be by her bedside instead of jumping at his last chance at super-stardom. As for Stella? She doesn’t know how or why, but she won’t stop drawing.

In best-selling novelist Caroline Leavitt’s newest novel, With Or Without You, she dives once again into the mind of a coma patient, exploring the profound ways that medical trauma can transform and haunt you, or even remake you. In a beautiful story of love and rediscovery, Leavitt explores the connection between fame and success, the creative impulse, and the heartbreaking ways our parents disappoint us. With Or Without You is a character-study disguised as the rarest kind of love polygon — one where not only does everyone deserve a happy ending, but where that happy ending isn’t what you’d expect.

To start, you cannot possibly have imagined while writing this novel that it would be released at a time when the very idea of medical professionals being in comas would conjure such incredibly specific visuals and emotions. We’re seeing stories about this all the time now. How does it feel to be releasing this book during the pandemic?

It feels distinctly weird. I was in the zone of writing for so long, being in an altered reality, that when the real altered reality of the pandemic hit, I was gobsmacked. I could never have imagined this constant worry, though my husband Jeff told me that the only other time before the pandemic that he ever felt this sort of dread was when I was in coma.

As a new mother, I’m really drawn to the parallels between comas and childbirth — the rewiring of your brain and the discovery of a new “self,” both mentally and physically. In the Daily Beast, you wrote about your coma as primarily a physically transformative experience — coinciding with motherhood for you. In With or Without You, she comes out of her coma as a new person, mentally. Do you see a connection between the transformative power of comas and motherhood and do you ever feel those experiences have been entangled for you?

Oh definitely. I came to motherhood late in life after a series of miscarriages and when I was pregnant, I began to feel that difference. I felt my son’s presence. I sang to him, talk to him, played him music, because I had read that the mother’s emotions can impact the child. And when he was born, there was that other difference. Even now, when I see babies or children, I want to hold them! I definitely think your brain gets rewired, and I read in my research, which fascinated me, that some of the mother’s memories do go into the fetus DNA, and vice versa. And they STAY THERE. Isn’t that amazing?

I am struck, also, by the connections between Pictures of You and Without or Without You. Two women, both desperately desiring children, both able to create visual representations of intangible traits, both with cheating partners. Is there something about the desire for children, and inability to have them that you believe allows these characters to see or intuit things about the people around them? Or is it the knowing-but-not-knowing underpinning their relationships and their partners’ infidelities that drives these abilities?

What a great question. When I was so desperate to have a child, and wasn’t succeeding yet, I threw myself in my work and it helped, but only some. In my first marriage, my husband was a serial cheater, and on some level back then I felt if I had a child, I’d have someone to love me, but at the same time, I knew I could not do that with this person! I also think the not knowing for sure (I didn’t find out about his cheating until much later) ) definitely drew me more to my work because I had a sense I could at least control something, if only a little.

When Stella wakes up, her desire for a child almost seems to have quelled, or at the very least she has come to some acceptance. Do you feel this is because the coma has served for her the same transformative function that motherhood would have? Or is it more that her creative impulse is being fulfilled by painting?

Another great question. Stella’s brain is rewired and it takes her a long time to find out who she is and what she wants—and her yearning for a child, which for her, was really to cement her relationship with Simon, to have something that was—and wasn’t her—a child, was unwired.

Stella and Simon represent two very different stances on fame, success, and creative output. As a best-selling author, do you see your success as Stella does — as the means of continuing to create — or more as Simon does — as the ends, themselves?

Another important question. I thought a lot about fame. I wanted it desperately when I was first starting out as a writer and I had it for my first book, and then not for another 8 books! I came to realize that fame is really, at least it was for me, a yearning to be seen, to be recognized as someone worthy, which was something I didn’t have in the family I grew up in, except for my mother. When my 9th novel, Pictures of You, was rejected on contract as not being special, I thought my career was over. Who would want to publish someone who had no sales? But Algonquin saved me and turned the book into a NYT Bestseller and got it into 6 printings before it was even out! But I felt differently about it then—I came to realize that it’s much more important to have one person who loves you and appreciates and knows you then it is to have millions of fans. I’m really on the Stella team, here!

Stella is on the page in her own words very infrequently for the first hundred pages. We see her as Libby and Simon see her, and as she is in her coma, but we have a fairly brief introduction to her as she saw herself before the coma. How much of a challenge did that pose for you, when writing the distinctions between who she was pre- and post-coma? How did you know that was the right decision?

It was really difficult. I knew I had to have Stella go in coma fast, but I also had to keep things happening without forgetting what was going on with Stella. I did a ton of research on coma and talked with a researcher, Joseph Clark at the University of Cincinnati, a lot, so I knew what could be possible and what couldn’t. It was like this menu I got to choose from!

All three of your narrators have distant, largely unsatisfying parents. You could even argue that the relationships between parents and child are the wounding events for each of the narrators. All of the parents are redeemed to varying degrees by the end of the book — I’m curious how you see these parent-child relationships and what they mean for each narrator.

I grew up in an unhappy family. My father was a silent abusive brute, my mother could be fiercely loving but she was so unhappy that she would sometimes rage, and my beloved older sister has estranged herself from me—something that began happening when I was 17. So I know how difficult it is to grow up in a family where you are always yearning for someone to see you, to praise you, to love you, and you are always somehow getting the opposite. Those wounds are really hard to heal because often the price is letting go of them and realizing that well, maybe, you are NEVER going to get that love or that appreciation. For some of my characters, those wounds are based on misconceptions, which can be healed by new information or action, like with Libby. For others, like Simon, he has to come to terms with what is real as opposed to what he wants. And for Stella—well interestingly enough because she’s a painter, she simply was not seeing the whole picture.

Obviously, music is an influence on you — what music would you say has been the biggest influence? What did you listen to while you wrote this book, and is it different from what you listened to while writing other books? What has the soundtrack of your quarantine been?

I just did a playlist for the wonderful Largehearted Boy!

It always is different depending on what I am writing. If I have to write a scene that is going to gut me, my go to music is Crowded House, especially Don’t Dream It’s Over. If I’m writing something happy, The Beatles!

What creative outlets do you have when you’re not writing? How do they fit in with and influence your writing, if at all?

I used to be a painter. I even had a scholarship to go to special classes at Mass College of Art while in high school. But I gave it up seriously because I loved writing more. I still paint watercolors, but for friends, and for myself.

I also knit. I find every stitch somehow heals me. I used to design sweaters (I made one years ago for my first husband with dinosaurs grazing on vegetation front and back, but I scissored it up when I discovered he was cheating! I wish I still had the sweater). I didn’t go back to knitting until the pandemic when a therapist told me that that small motor skill would help with anxiety. I’ve made six sweaters! I love it!

And I watch movies.

All of it feeds creativity, I think.

What question do you wish people would ask that they never do?

Oh I love this!

What crazy things do you believe in?

I believe in psychics, tarot cards, palm reading, ghosts, haunted houses, too. And not in a woo-woo way, but I assume it all somehow has to do with quantum physics.

Caroline Leavitt is the New York Times bestselling author of 12 novels, including Pictures of You, Is This Tomorrow, Cruel Beautiful World and With or Without You. A former New York Foundation of the Arts Fellow, she was also a finalist in the Sundance Screenwriters lab in Pilot and Features. A book critic for People and AARP, she is also a columnist/blogger for Psychology Today, and her essays have appeared in New York magazine, “Modern Love” in the New York Times, The Millions, The Daily Beast, The Manifest-station, Salon, Lit Hub, and more. She teaches novel writing online for Stanford and UCLA Writers Program Extension, and works with private clients.