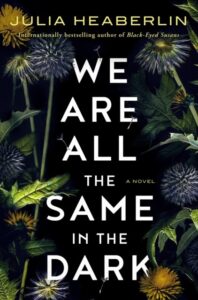

Beautifully sharp and atmospheric, We are All The Same in the Dark by Julia Heaberlin is a haunting psychological noir that starts with a girl found in a field and ends in revelations that redefine a small town’s mythology. It is written from three points of view (with varying degrees of reliability): a secretive man who has become the town pariah, an ambitious young female cop, and a one-eyed mystery girl. An unsolved murder brings them all together in profound and disturbing ways.

Beautifully sharp and atmospheric, We are All The Same in the Dark by Julia Heaberlin is a haunting psychological noir that starts with a girl found in a field and ends in revelations that redefine a small town’s mythology. It is written from three points of view (with varying degrees of reliability): a secretive man who has become the town pariah, an ambitious young female cop, and a one-eyed mystery girl. An unsolved murder brings them all together in profound and disturbing ways.

The starred review in Publishers Weekly says it well: “After a devastating twist halfway through, the intense plot builds to an emotional finale. Heaberlin sensitively addresses issues of survival and vulnerability in this heart-wrenching gothic tale.”

Julia, it might be an understatement that you do not shy away from characters suffering from trauma, using all that pain to highlight our flawed humanity and search for grace. How do you think about this when you sit down to write? You nestle up to a whole lot of dark, and I don’t mean the kind that only comes at night.

If you’d asked me this question before We Are All The Same In The Dark, I would have said I was able to write dark subject matter because when I shut the computer, I went back to a lucky, happy life. I still feel lucky. Happy. But the year I wrote this book was one of the toughest in my life. After a tragedy happened to a friend of mine, I woke up every morning wondering if it was a dream. I felt physically changed, as if I would never be the same. I became intensely bothered by inanimate objects in my house—a necklace, a piece of “good luck” quartz, a staircase. I think this book, in many ways, is an extension of that grieving experience, of PTSD, of questioning randomness, God, the route to recovery. I was sensitive to this kind of trauma before—I wrote all over it—but I never understood it like this. I learned it’s much harder to write about dark places when you are in one yourself.

You’ve said before that secrets, lies and the capacity for forgiveness lies at the heart of all of your novels, and this one is no exception. You’ve also said you are fascinated by true crime and how events play out years later. Why the return to this theme? In other words, talk to me about your obsession(s).

My list of obsessions is long—buried objects, small towns, old houses, Texas, bones, DNA, black-and-white photographs, the creepiness of nature.

So I will stick to the theme of victim vs. killer, the graphic vs. the psychological. Why do we know much more about Ted Bundy than the women he killed? Why do news stories focus on the act of the horror and much less on the psychological damage it leaves behind? I set out to write books where women are both the victims and heroes of their stories. Where they star. And where the tension works in tandem with your imagination. As for redemptive endings, I don’t like books that don’t have one. So I don’t write them. I want to walk away at the end of the book, no matter what scary or disturbing thing I’ve conjured up, knowing there is hope.

I loved how the new documentary about Trumanell’s murder put the entire town on edge. It was a brilliant way to bridge the time gap and explore how this does and does not change people and what they believe. What were the advantages and disadvantages to structuring a novel covering so much time?

My British editor, Maxine Hitchcock, is obsessed with crime documentaries so a shout-out to her for pushing me to sharpen and enhance this aspect of the novel. I found the structure primarily an advantage. I liked returning to the same places with new eyes—in particular to the two secretive old houses. The reader knows what is there sometimes before the character does. It was fun to play around with.

I gasped at the plot twist about halfway through. This is difficult to talk about without spoilers, but do tell me the story about how you arrived at that shocking twist and if you faced any editorial resistance.

After I wrote it, I gasped myself. I don’t outline. I always say that the characters lead the way, so in this case, it was the oh-so-fierce Odette, one of my two heroines. The twist was unlike anything I’d ever done before. I asked myself a hundred times if it was fair, organic, true to the kind of books I want to write. But I couldn’t see it any other way. And, yes, I expected some editing blowback. Instead, not one of the five editors/agents who did early reads suggested changing it.

Ocular prosthetics play a big role in this book, and you tell us all about your detailed research in the Acknowledgments. Can you tell us how you balance your research and writing? Any tips for the writer who finds organization difficult?

Every time I research, I’ve been knocked back by incorrect assumptions. So it’s critical, adding layers to the plot and characters. But I’m not systematic—I’d describe my research process as thorough but schizophrenic. I use a lot of Post-it notes. I might do some significant research ahead of time—like interviewing a DNA expert who identifies old and degraded bones. Or I might tackle it halfway through, like in Black-Eyed Susans, when it finally struck me that the theme of the novel was the Texas death penalty.

I didn’t have a specific plot in mind when I began to write We Are All The Same In The Dark. I was just haunted by a visual of a girl with one eye. As soon as I started to put her on paper, she was a big cliche. That’s always the beep-beep of the research alert. My advice: When you’re stuck, you don’t know enough about what you are writing. So stop. Pull books out of the library. Call or email an expert. And realize that six hours of research might result in two paragraphs of authenticity. But those are very important paragraphs.

You capture the heat, expanse, religion, guns and attitudes of Texas as a place but also as a state of mind. It feels so complex and real. What advice can you give about what you do so effortlessly, in making Texas a character?

It is just part of me, a second skin. I’ve slept in its dark heat most of my life. I’ve observed its flaws and beauty since I was three. I’ve been mentally unable to keep it out of my books. It’s always a character as big as any other.

On your website you write eloquently about your difficult path to publishing. What do you wish you had known ten years ago?

That publishing is a business like anything else, full of fools and geniuses. Yes, it was hard to get published. But it was honestly worse being dropped by my publisher before publication of my second thriller. For months, I thought my career was over. Because of a supportive husband and agent, and a last scrap of ego, I persisted. The publisher who rejected me was fired. And the book she rejected, Black-Eyed Susans, went on to become an international bestseller and has now been optioned by Sony Pictures for a limited TV series. That was a painful lesson with a happy ending. I wish I could tell my old self: Chin up.

Thank you for these especially thoughtful questions!

Julia Heaberlin is the author of the international bestseller BLACK-EYED SUSANS and PAPER GHOSTS, a finalist for Best Novel of the year by the International Thriller Writers. WE ARE ALL THE SAME IN THE DARK, her latest psychological thriller, has received a starred review from Publishers Weekly. Her books have sold to more than twenty countries, including two other psychological thrillers set in Texas, PLAYING DEAD and LIE STILL. A journalist, she has long held an interest in true crime and its lasting psychological effects on victims. Her books have examined themes of the Texas death penalty, dementia, prosthetics, and the power of DNA technology. Before writing novels, she was an award-winning editor for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, The Detroit News, and The Dallas Morning News. (Almost) a native Texan, Heaberlin lives in the Dallas/Fort Worth area where she is at work on her next book.