It’s been said lots of times, in lots of different ways, that any good novelist must have something burning inside him or her; something that absolutely has to be said. It burned white- hot in Richard Yates. Though racked in mind and body and spirit for most of his life, nothing could stop him from writing. Nothing.

It’s been said lots of times, in lots of different ways, that any good novelist must have something burning inside him or her; something that absolutely has to be said. It burned white- hot in Richard Yates. Though racked in mind and body and spirit for most of his life, nothing could stop him from writing. Nothing.

He found himself, from time to time, in varying states of psychosis, triggered by inhuman volumes of alcohol, mixed with the psychotropic drugs the shrinks were pushing on him in the seventies. True, he’d been sternly warned not to mix the booze and the prescriptions, but an irascible Yates could be counted on to listen to his muse sooner than a bunch of damned old doctors. In one draining breakdown, a raving, delusional Yates, Boston-based at the time, was picked up for public drunkenness in Harvard Square. The cops moved him to a dry-out facility and, shortly thereafter, friends arranged transfer to a (locked) ward in the Jamaica Plain VA hospital. His mind cleared after a few days of alcohol withdrawal, and when the friends came to see him, he was sitting up with a typewriter mounted on that narrow little table they swing across a hospital bed. He was typing, quietly and industriously, the manuscript to Cold Spring Harbor.

His lungs were ruined early on, starting with acute pneumonia, suffered as an exhausted nineteen year old soldier in France, during the wintry, waning days of World War II. Don’t smoke, army doctors told him on discharge. You’re at risk for TB, they told him. Sure enough, the chain-smoking young veteran landed himself in a VA- run TB hospital, within a few years of the war. He beat the TB, eventually. Still, he smoked, one decade rolling into the next. Smoking and drinking, drinking and writing. Then smoking and writing and drinking some more.

He moved to Boston in the mid-seventies after a series of personal disasters in New York. A decade and a half earlier, he’d published the modernist masterpiece, Revolutionary Road. A New York Times review called it a “remarkable and deeply troubling book — a book that creates an indelible portrait of lost promises and mortgaged hopes in the suburbs of America.”

It was his first novel and, most critics agree, the jewel in his literary crown. Like most of his work, it was highly autobiographical. In it, April Wheeler, an integral character and wife to the protagonist, declares, “[I]f you wanted to do something absolutely honest, something true, it always turned out to be a thing that had to be done alone.” Perhaps it’s what Yates had in mind when he moved to Boston in 1976, setting himself up in a squalid little apartment no more than a hundred yards from the Crossroads Irish Pub on Beacon street, where he would eat almost every lunch and dinner in the eleven years he spent in Boston.

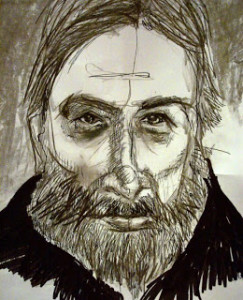

He was fifty at the time, survivor of two ruined marriages, scruffy and dissipated in such a way that the Crossroads waitresses thought, on first glance, he was a homeless person – an unseemly persona for a writer whose superb novel Easter Parade had recently been released down in New York. Critics and writers raved. Kurt Vonnegut likened Easter Parade to Madame Bovary.

But some feared the increasingly erratic Yates, self-exiled to a Dostoevskian hovel in Boston, was all done. This once-strapping, looks-to-die-for literary star, one-time teacher at the Iowa Creative Writer’s Workshop, all done? It seemed impossible. Still, the once buttoned-down speechwriter for Robert F. Kennedy, was “hacking, muttering and mad,” when he got to Boston, in biographer Blake Bailey’s own words. Was he too far gone?

Yates knew better. His rigid sense of writing discipline had remained unbent, and it was all that was important. In the essay, “A Salute To Mr. Yates,” his good friend, novelist Andre Dubus, described a typical day in Boston. “He woke each morning at seven and ate breakfast, then worked till noon, when he walked perhaps a hundred yards to… a restaurant called The Crossroads. After lunch he went to his apartment for a nap. Then he wrote till evening and returned to The Crossroads for dinner”

Bailey tells us the waitresses (who’d grown quite fond of him) put the time Yates was gone to good use: “wiping down [his booth]… from all the ashes scattered by his explosive coughing.” The biographer adds, too, that Yates stayed at the Crossroads after dinner. “By ten o’clock, usually, he’d drunk enough Michelobs to face his dark apartment and get some sleep.”

From that mad and tortured time forward, Richard Yates completed four more highly regarded novels.

“I don’t want money,” he told Dubus. “I just want readers.”

Drinking and coughing. Coughing and writing and drinking some more; burning – white hot – with something to say.

He left Boston for good in the late eighties, and lived with his daughter, Monica, mostly in Los Angeles. He was sent to a VA hospital for hernia surgery in 1992. Left alone and unattended one night, a coughing attack led to unrelieved retching until he choked and he died.

Finally, the writing had stopped.