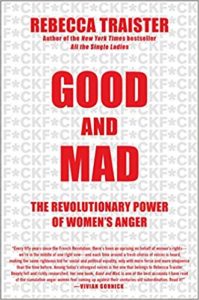

In Rebecca Traister’s newest tour de force, Good and Mad (Simon & Schuster, 2018), she shares a memory from an early job in a male-dominated office where she found herself weeping in inexpressible rage. A female colleague dragged her into a stairwell to say: Never let them see you crying. They don’t know you’re furious. They think you’re sad and will be pleased because they got to you.

In Rebecca Traister’s newest tour de force, Good and Mad (Simon & Schuster, 2018), she shares a memory from an early job in a male-dominated office where she found herself weeping in inexpressible rage. A female colleague dragged her into a stairwell to say: Never let them see you crying. They don’t know you’re furious. They think you’re sad and will be pleased because they got to you.

Traister builds on this memory to expertly argue that tears are the most frequent outlets for women’s wrath and “the fact that they are permitted is in part because they are fundamentally misunderstood.” I read this the day I watched Serena Williams battle chair umpire Carlos Ramos. There was the best athlete the world has ever seen penalized because Ramos, as Sally Jenkins wrote in the Washington Post, “wasn’t going to take it from a woman pointing a finger at him.” But while Jenkins stood up and called Ramos out, so much of the other press I saw and read highlighted the tears from both Williams and her opponent and I couldn’t help but think Traister had nailed it—again. Those were tears of rage. In order for the world to understand this, and what really happened on court that day—they must read Traister’s book.

Good and Mad is a brilliant history of female anger as political fuel, from suffragettes to #MeToo. Just published and it’s already being lauded as fiery, fierce and timely and I couldn’t say it better myself. Traister’s dazzling research and ideas left me breathless as she laid bare the modern and historical relationships women have had with anger and the ramifications of expressing and suppressing it—and the despicable double standards used to silence women who dare to show rage. Traister’s ultimate message to us all: Don’t ever let them talk you out of being mad again.

Read this book. Read all of Traister’s books. They won’t disappoint and you will walk away with a new understanding of just how important anger is—that all revolution depends on it. We at Dead Darlings were thrilled when she agreed to this interview, so let’s get to the good stuff:

Rebecca, there was a warmth to this book that made me feel as if rather than reading your pages, you told me everything while we shared a bottle of wine. I can’t imagine how hard it was to write something so personal this well. Can you tell us if it was as hard for you as I imagine? For all our writers out there, can you offer any tips on how you did it?

It was a wonderful relief to be able to get so much of what was bubbling in my head out! I don’t mean to suggest that writing—the act of sitting down and putting sentences on a page—wasn’t hard. I wrote this book very quickly—in four months—and during those four months, there were stretches of weeks in which I didn’t really write a word. Then 2,000 words would come pouring out. But mostly, having never written a book so swiftly, I can say that it was, comparatively, a pleasure! Truly, a kind of catharsis.

While you wrote Good and Mad in a matter of months, the research and ideas must have been stirring around for a while. Can you tell us how long you’ve been stewing over the power of women’s rage?

I didn’t put the frame of anger on it until early 2017, but yes, these stories, this history, these politics, have been undergirding so much of what I write about for so long. I’ve written about the Anita Hill hearings in every one of my three books: I see it as a crucial moment of our lifetimes, a fulcrum moment. And as I compose my answers to these questions, it’s the night before the Brett Kavanaugh hearings, which are happening as a result of women coming forward as part of #metoo, a wave that happened, in part, because women were so angry after the election of a multiply accused predator to the presidency. Women’s anger is the tide that has carried us here, by many measure.

Most of our readers struggle with the question of how much research should be book/periodical based v. interviews. How do you think about this balance?

I never think about it too precisely. I cite a lot of books and media, and I usually do a lot of interviews and always wish I’d done more. I don’t have any particular measure or metric for this, and I fear I probably don’t get the balance right, a lot of the time.

Moving along to content. You shared that while writing this book, “There had been something about spending my days and nights immersed in anger—mine and the anger of others—that had been undeniably good for me.” This was one of my favorite passages because it flies in the face of what I was taught—what you say you yourself and so many other women were taught—that anger is a destructive force to tuck away. How did you come to think of anger in this new light? Did it happen suddenly, like a eureka moment?

Yes, it really happened at the end of the writing process, and I began to go back and look at the introduction I’d written four months earlier. I had a paragraph in that original introduction in which I’d written that while of this was a book that sought to value women’s anger, I of course also understood that too much anger could be bad for your health, etc. When I read that again, four months later, I realize that the four months I’d gotten to spend immersed in my own rage and taking seriously the rage of other women, had been some of the most purely healthy months I could remember: I’d slept well, eaten well, had a lot of energy. I began to think about how perhaps it was the bottling up of anger, rather than the anger itself, that raises our blood pressure and makes us grind our teeth.

In Good and Mad you recount an NPR interview with Rose McGowan, one of Weinstein’s most vociferous accusers, in which she was asked ‘What if what you’re saying makes men uncomfortable?’ She replied, ‘Good. I’ve been uncomfortable my whole life. Welcome to our world of discomfort.’ I imagine this book will similarly make a lot of people uncomfortable. And I think that is one of the key takeaways. Given that, how do you think you’ll confront that discomfort coming from critics and reviewers? I know you don’t have a crystal ball—but do you have any ideas you might be willing to share?

Oh, I hate reviews, honestly. I wish I were cool about it and thick-skinned, but the truth is that I’m very critical of my own work, and I always wish I’d had another week, another month, another year to make it better. So every bad review I read—from a smart reviewer, anyway—will make me think “oh yeah, that did kind of suck.” Except of course the bad reviews from those who are ideologically opposed. Those bad reviews I’ll relish. I’m sure there will be anti-feminist critics, or apologists for white patriarchy, talking about how unhinged and violent and dangerous and unpleasant my rhetoric is. But those I don’t mind.

Last content question. You wrote: No, I had never been serially sexually harassed. But the stink got on me anyway. I was implicated. We all are, our professional contributions weighed on scales of fuckability and willingness to get along, to be good sports, to not be humorless scolds or office gorgons. I imagine every woman knows exactly what you mean. How can we keep ourselves from being implicated? Any advice for those of us looking to balance the need to get along with coworkers and the instinct to fight? Or is that your point, there is no balance?

I think that on some very broad level, when we participate in the system as it’s set up—white capitalist patriarchy, we’re implicated. This is not about purity, getting pure. It’s about recognition of the role we all play, and yes, if we can find places in which we can challenge the abuses and injustices in the system, resisting those abuses. But I write about complicity not because I want to point fingers. I’m really just trying to raise consciousness, make clear the ways in which the system all around us is broken and supports various abuses of power, and that we all need to get better at seeing and acknowledging that, and to some degree acknowledging our role in it, with an eye to working together to make the system better and perhaps, one day, remake it.

Finally, let’s get personal. The one question I love to ask every author: What are you reading now? What books do you recommend?

I just started Tayari Jones’ An American Marriage, which I’m late to because I was writing my book. Before that, I read The Power by Naomi Alderman, which I kind of felt was like the fictionalized version of my book!

About Rebecca Traister: is writer at large for New York magazine and a contributing editor at Elle. A National Magazine Award finalist, she has written about women in politics, media, and entertainment from a feminist perspective for The New Republic and Salon and has also contributed to The Nation, The New York Observer, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vogue, Glamour and Marie Claire. She is the author of All the Single Ladies and the award-winning Big Girls Don’t Cry. She lives in New York with her family.

2 comments